Friday Frivolity no. 15: Time for Tea

tea's history, teatime recipes, and the beau-tea of it all

This is an installment in the section Friday Frivolity. Every Friday, you'll get a little micro-essay, plus a moodboard, 3 things I'm currently in love with, words of wisdom from what I've been reading lately, a shimmer of poetry, a "beauty tip," and a question to spark your thought.

also you can find more of me on Tumblr and Twitter hehe

—

Time for Tea

In a year not far into the future, tea will come into our homes through pipes. One will have a little faucet by one’s nightstand; one only need place a mug under it, turn the tap, and the beautiful decoction, piping hot, perfectly brewed, Earl Grey or English Breakfast or Darjeeling or what have you, will come out, ready for milk, sugar, and immediate consumption. People could have such faucets installed in their kitchens, in their studies, by their desks, in their cozy reading nooks. In an age when it is possible for cars to parallel park without drivers and machines can pen (bad) Shakespearean sonnets, why someone has not yet seen to bringing this all-important invention, this crucial contrivance, this absolute necessity of modern life into reality mystifies me, truly.

I am sure that our household would not be the only beneficiary. However, I must concede that tea is one of our house’s particular load-bearing pillars. The day begins and ends with the whistling of the electric kettle; no day is complete without it. Making tea for someone is a love language in our family. When my father was alive, the first thing he would do in the morning is go down to the kitchen, summer or winter, hot or cold, sunny or rainy, and brew a cup for my mother and himself, then carry the two teas upstairs, one to greet his wakening wife, the other to sip as he perused the news and scrolled through headlines. I always had my tea later, at breakfast; around 10 in the morning, they would have a second tea; the third tea was at teatime, 3:00 PM, the crux of the day, the hour that everyone looked forward to, the hour—“tea o’clock,” my father and I called it—when we would all find respite in sitting around the table, exchanging snacks and conversation, looking out at the squirrels and the rabbits through the window, observing the minutiae of the seasons’ changing, warming our hands around that steaming liquid hug.

When my mother wanted to literally spice up an afternoon, she would make masala chai on the stove, in the traditional way, always strong and thick and aromatic. Around 6:00 PM, when my parents were finished with work and the ennui of the evening started to set in, we would rev ourselves up with a fourth cup, and though I never had tea after dinner, my parents always had their fifth cup before bed—how they could fall asleep with all that late caffeine I have no idea, but that they woke up and went to bed with tea speaks to its dual nature, in equal parts stimulating and relaxing, quickening in the morning, quieting in the evening. The right to an extra sixth cup was reserved for especially cold, snowy days, gloomy, rainy days, or days that were sluggish and needed an extra boost of warmth or reassurance or caffeine. This may seem excessive to some, but we are one shy of Lu Tong’s seven bowls, and compare us to Padma Lakshmi, who can boast a heaping 12 cups a day, and you will see that we are amateurs.

Tea’s history is a tangled one. Look deeper into the murky dregs, and you will dredge up revolutions and wars, smugglers and thieves, fortunes and ruins. Its beginnings are shrouded in mists as fine as those that rise in the eastern blue hills where Camellia sinensis has been cultivated, grown, and picked for centuries. In the Yunnan province, where lush forests swathe China’s rugged borders with Laos and Myanmar, the fertile land watered by the Mekong River gives rise to seven tea mountains, still revered by the Dai and Bulang minorities. The leaves were first consumed for their medicinal properties, boiled with several other plants, seeds, barks, and leaves, then consumed alone, spreading to other provinces. First dried, charred, and then boiled, tea was a bitter drink; pounded, compressed into small baked cakes, from which pieces were chipped and steamed, it gained sweetness. Refinement of tea etiquette arrived with the Tang dynasty, who formalized tea gatherings, and highly ranked families all employed expert tea masters, following rituals like those codified in Lu Yu’s The Classic of Tea. Tea continued to spread, planting new rituals in Japan; the leaves began to be powdered and whisked into green froth; teapots, bowls, cups, saucers, and Europeans arrived.

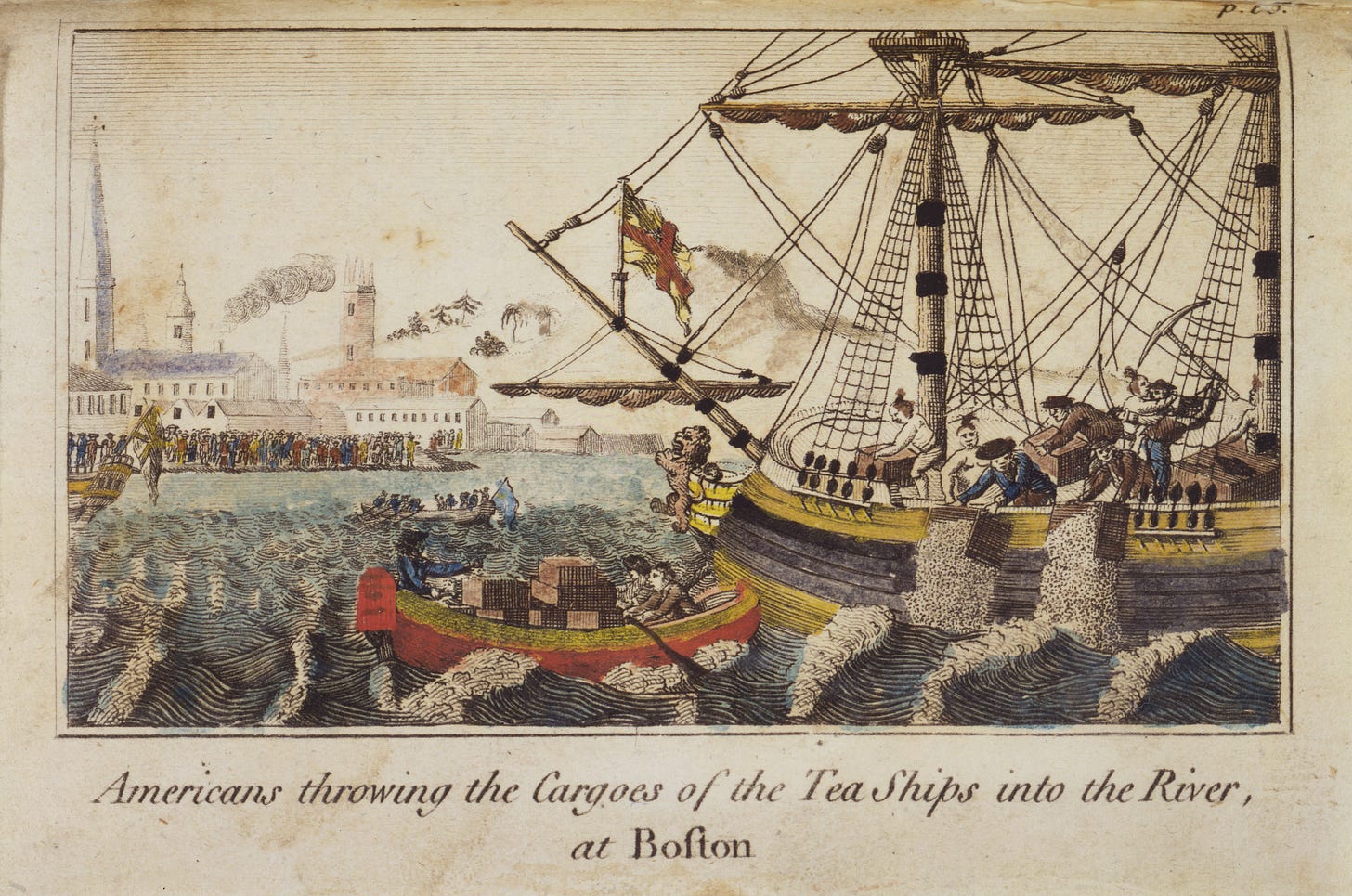

It was the Dutch, establishing a foothold for themselves in Jakarta, who first caught tea fever. For them, Chinese tea merchants perfected a black tea, able to withstand the long, damp voyage to Holland in a way the more delicate green tea was not. By way of the Dutch trade, tea appeared in Massachusetts in 1670, and the Dutch also brought it to England, where, mixed with milk and sugar (imported from the West Indies), it sparked a craze that has yet to end. Perhaps it would have been better for the fate of tea in America had the Dutch continued to control the trade; in 1773, an estimated 18,523,000 cups of tea were dumped into the Boston Harbor, where the fish, perhaps, now imbibe it, enjoying its centuries-long steeping.

For 150 years, the English East India Company had exclusive rights to bring Chinese tea to England, but when the monopoly ended in 1834, they found themselves in a bit of a conundrum. China was not exclusive, Indonesia was controlled by the Dutch, and only India, with no established tea cultivation, it was thought, remained. But there were rumors that in the valleys of Assam, in the northeast of India, a different variety of tea bush grew, whose leaves were fermented and drunk by the Singpho tribes. This Assam tea did not look like the Chinese tea, and, desperate for the Chinese tea secrets, the English used opium, war, and yellowface subterfuge by Scottish botanist Robert Fortune to attempt to match a knowledge and production perfected over thousands of years. Finally, they prevailed, turning India into the largest tea-producing country in the world and severing ties with China, a staggering blow the Chinese tea industry would not recover from until the end of the 20th century.

Today, tea production has spread to over 45 countries. It is the second-most consumed beverage after water. Therefore, let the next chapter in the history of this delightful drink be tea pipes in our houses, I say. But then, is it not the process of brewing itself, the waiting and the boiling and the steeping and the steaming, the additions of herbs or dried fruit, spices or flowers, milk and sugar, the billowing fragrance, the warmth and aroma curling up to meet one’s tired face, in need of cheering, the first tentative sips, the almost sacred savoring, that makes this little leaf so special?

Mood Board of the Week

(left to right, top to bottom)

Tea at Bistro du Vin, photographed by Hotel du Vin & Bistro: I always loved these little tiered cake stands—adorable, proper, varied, delightful.

Photograph by Hanna Stefansson of Flickorna Lundgren in Sweden: I love this photograph for the way it evokes the simple joy of sharing a little treat—and a moment of tranquility—with a friend. Apparently, Flickorna Lundgren is Sweden’s oldest garden café, started in the small fishing village of Skäret in 1938 by the seven Lundgren sisters. It has the adorable look of a simple country cottage or Snow White’s house with the seven dwarves—I wonder if the eight of them used to have tea together.

Afternoon tea by isolano on Flickr: Gardens cafés are good for spring and summer, but when the temperatures drop and the weather gets gloomy, you need something warm, cozy, dry, and with a good roof above it and four sturdy walls. If it also has impressively large old paintings, charmingly old-fashioned wallpaper, and eccentrically matching chairs and tables—as this café does here—so much the better.

Teapot with Pattern of the “Hundred Antiques,” China, 19th century, The Met: The “hundred antiques” was a pattern that became popular in 17th-century China, featuring ornamental vessels, the items of scholars, and other antique objects. Its popularity grew over the Qing dynasty, and it was often made into rebuses meant to symbolize auspiciousness. This particular teapot has so many cheerful colors and vibrant patterns on it that I’m sure I could use it for tea everyday and never ever get bored.

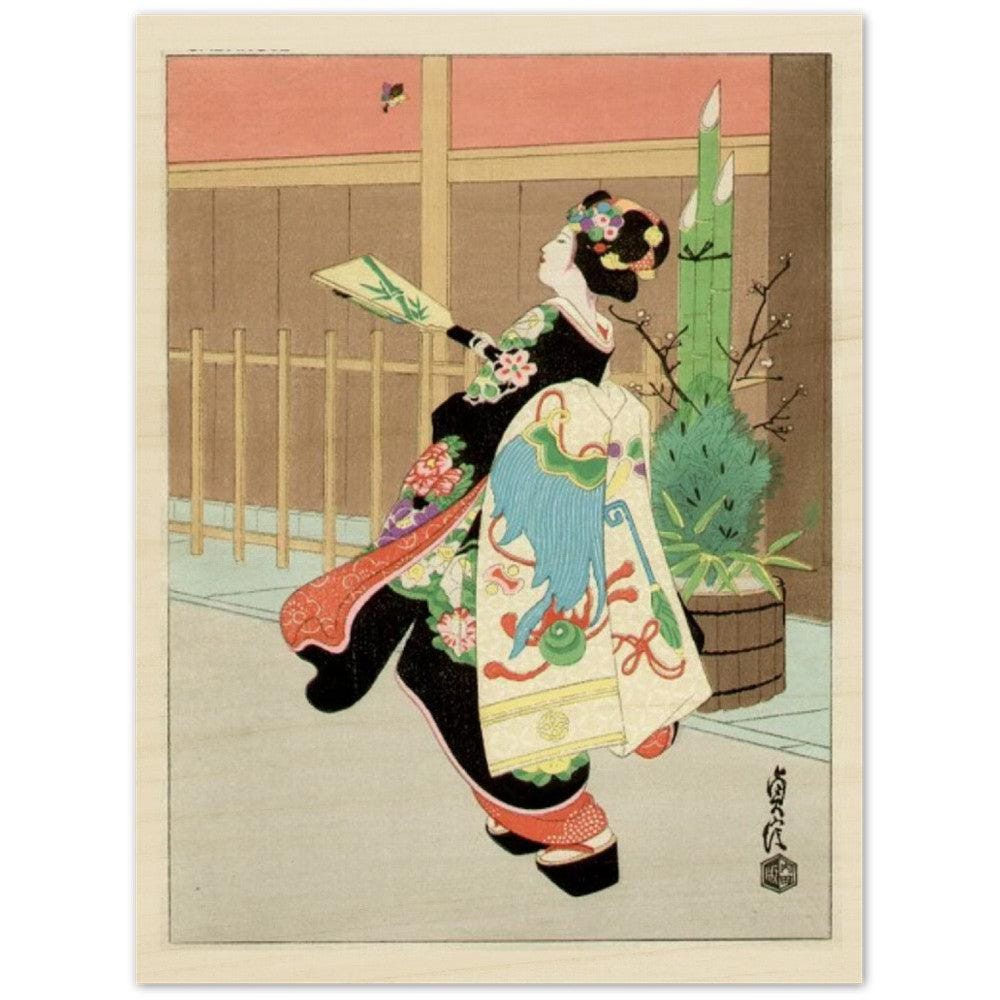

Hasegawa Sadanobu III, Kyo-Maiko (ca. 1950s): Hasegawa Sadanobu III (1881-1963), also known as Konobu, was a Japanese woodblock print artist who was the third to inherit his family’s prints business. His early landscape work was inspired by his grandfather, but he later became sought-after for his depictions of beautiful women, drawing out the intricate details of their dress. Although he accepted some Western influences, his work helped to revive traditional Japanese woodblock printing while also incorporating a modern flair. In this print, he shows a maiko, an apprentice geisha. The fourth in a series of six prints depicting a young maiko in traditional scenes, this one shows her performing a tea ceremony, following the “Way of Tea,” which has its roots in Buddhism and honors four key principles, “harmony,” “respect,” “tranquility,” and “one time, one meeting” (the idea that each meeting is unique and therefore to be treasured). Becoming a master of this art can take many years of practice, just the sort of practice this young woman is getting in here.

Emmanuelle Béart photographed by Tony Frank in 1985: To be honest, I’m not really sure whether French actress Emmanuelle Béart (who stars in one of my favorite movies, Jacques Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse) is drinking tea or coffee here, but either way, the lovely simple china, the oranges, and the warm dreamlike light settling on Emmanuelle’s skin are everything I want for a cozy teatime experience.

Afternoon tea, photographed for Hotel du Vin & Bistro: The green Swiss roll (pistachio?) and white macaron are very intriguing to me. Who can resist the adorable delicacy of little pastries?

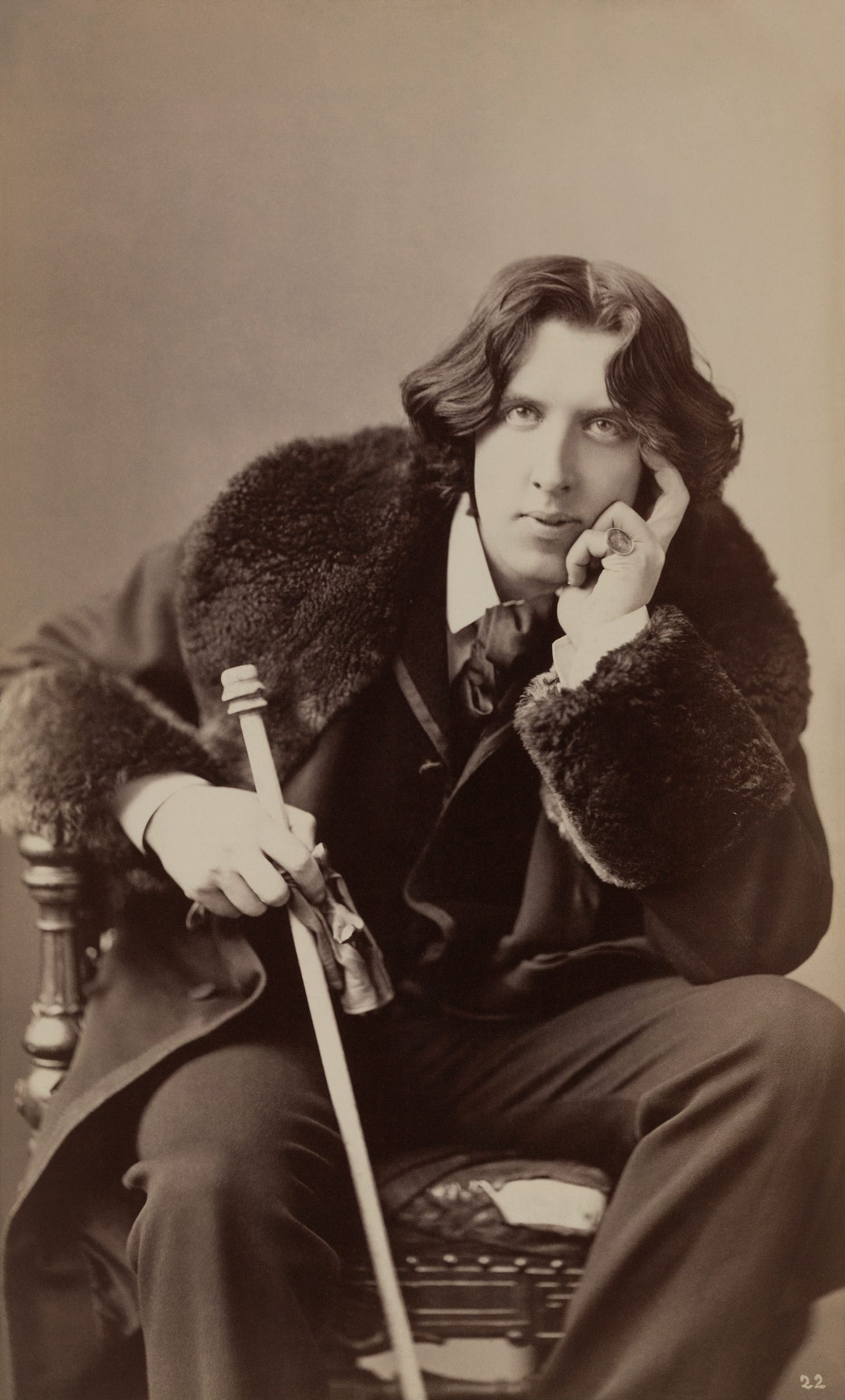

Colin Firth as Jack Worthing and Rupert Everett as Algernon Moncrieff in The Importance of Being Earnest (2002): Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest is one of my favorite plays ever—it’s so funny and silly and witty, and who can forget the incomparable Lady Bracknell? In the play, Wilde pokes fun at the Victorianisms of the upper class, and one such Victorianism was the rather new British obsession with afternoon tea. The play begins with Algernon Moncrieff eating all the cucumber sandwiches intended for his aunt, Lady Bracknell; later on, a monumental scene between the four principal characters takes place around teatime. Gwendolyn and Cecily, both under the mistaken presumption they are in love with the same man, glare at one another, and the tea table becomes a battleground.

Cecily asks Gwendolyn if she may offer her some tea; Gwendolyn, in an aside, says, “Detestable girl! But I require tea!” Cecily offers sugar. Gwendolyn replies, “No, thank you. Sugar is not fashionable any more.” Cecily proceeds to give her four lumps of sugar. Cecily then asks Gwendolyn whether she would prefer cake or bread and butter. Gwendolyn replies, “Bread and butter, please. Cake is rarely seen in the best houses nowadays.” Cecily gives her “a very large slice of cake.” Only once the servants are out of sight can Gwendolyn give full vent against these insults: “I warn you, Miss Cardew, you may go too far.” However, they soon find out the truth, which puts the men—Jack and Algernon—in hot water. Spurned by the women, they sit forlornly at the tea table. Algernon begins to eat muffins. Jack scolds him for “calmly eating muffins when we are in this horrible trouble.” Algernon’s reply is perhaps my favorite line in the whole play: “Well, I can’t eat muffins in an agitated manner.”

Victoria sponge photographed by Carwyn Lloyd Jones on Flickr: Around 1840, Anna Russell, the seventh Duchess of Bedford, invented the British custom of afternoon tea. The twin ills of industrialization and urbanization had widened the abyss between the midday and evening meals, leaving the Duchess with a “sinking feeling” in the afternoon. One of these afternoons, feeling rather more sinking than usual, the Duchess asked for tea, bread and butter, and cake to be delivered to her drawing room. A ritual was born, and she began to invite her friends to afternoon tea. One of those friends was Queen Victoria. Victoria took to the habit with gusto, and her repertoire of sweet treats to be washed down with tea included biscuits, petit fours, and chocolate sponges. In 1843, baking powder was created by Alfred Bird, making it possible for sponge cake to rise high and be light and airy. The result was Queen Victoria’s favorite teatime accompaniment: jam and cream sandwiched between two tall layers of sponge.

3 Things I’m in Love With This Week:

Teatime Recipes Edition!

Lemon Curd: Scones are traditionally served with jam and clotted cream and butter, but I recently tried the combination of scone and lemon curd, and it was fantastic—definitely adds a beautiful bright tang to your teatime that would be especially great in the summer. There are only four ingredients—eggs, sugar, lemons, and butter—in lemon curd, so it’s very easy to make, and it’s also very easy to store for later use.

Coronation Chicken Sandwiches: Coronation chicken was created by Constance Spry, an English food writer, and Rosemary Hume, a chef, for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953. Its bright yellow hue—thanks to a creamy sauce of mayonnaise, tomato purée, apricot purée, turmeric, curry powder, and other spices—always brightens a dull day. Its inspiration was apparently a dish created for George V’s Silver Jubilee, and, being served cold, was intended to suit the limited kitchen facilities of the Westminster School’s Great Hall, where the banquet took place. In recent years, it was updated into “Diamond Jubilee Chicken” for Elizabeth II in 2012 by Heston Blumenthal, who is such an enthusiast of the recipe that he even once made Coronation Chicken Ice Cream. Not sure that will catch on in quite the same way.

Persian Love Madeleines: Persian love cake is a special favorite of mine, and madeleines, those delicate, shell-shaped little cakes are so light, so sweet, and so delightful. I thought madeleines would be especially appropriate for this post because I always associate them with Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time and his famous madeleine episode, in which a madeleine dipped in tea prompts an involuntary remembrance of his childhood and his aunt: “No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin…. Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it?… And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray… when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. And all from my cup of tea.”1

These Persian love madeleines add an interesting twist to a classic recipe and also just look really pretty—how could you go wrong with rose petals? For a more authentic Proust experience, pair your madeleines with a cup of lime blossom tea!

Words of Wisdom

To love oneself is the beginning of a lifelong romance.

— Oscar Wilde, An Ideal Husband

In the mood board I included a scene from Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, and Oscar Wilde, as one of the foremost wits in the English language, always has something pithy, aphoristic, and wonderful to say. What truly amazes me about Wilde is not just his wit but also how good he was across a variety of genres—his hilarious comedies, his beautiful tragedy Salome, his great novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, his lyrical poems, his lovely fairy stories, his incisive essays like “The Soul of Man Under Socialism.” I highly recommend Richard Ellmann’s biography if you want to know more about his life and its relation to his work!

Poetry Corner

Yes, when all the world from Paris to China Pays heed to your doctrine, O divine Saint-Simon, The glorious Golden Age will be reborn. Rivers will flow with chocolate and tea, Sheep roasted whole will frisk on the plain, And sautéed pike will swim in the Seine. Fricasseed spinach will grow on the ground, Garnished with crushed fried croutons; The trees will bring forth apple compotes, And farmers will harvest boots and coats. It will snow wine, it will rain chickens, And ducks cooked with turnips will fall from the sky.

—Ferdinand Langlé and Émile Vanderburch, from Louis-Bronze et le Saint-Simonien

I encountered this fantastical snippet of poetry in Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, a vast compendium of social and historical research, literary references, poetry, and Benjamin’s own commentary, all uniting around the 19th century and its great upheavals. Taking inspiration from the iron-and-glass covered arcades that Benjamin saw as emblematic of the changes that urbanization and industrialization had wrought on 19th-century Paris, he organized his book into “convolutes” of topics as various as mannequins, the stock exchange, and Karl Marx.

Of the many new economic and political ideologies that proliferated in the 19th century, Saint-Simonism, advanced by the eponymous French aristocrat Henri de Saint-Simon, argued for a society governed not by the aristocracy or by politicians but by scientists, engineers, and industrialists, who would use their specialized knowledge to advance the collective welfare. To that end, property and economic resources would be centrally controlled by the state; workers would contribute according to their abilities and share in resources according to their contributions.

Poking fun at this philosophy, Ferdinand Langlé and Émile Vanderburch staged a three-act burlesque parody of Saint-Simonism at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal in 1832. I love all of the images in this little fragment, the rivers “flow[ing] with chocolate and tea,” the roasted sheep “frisk[ing] on the plain.” And who, especially at this autumnal time of year, wouldn’t want, instead of going apple picking, to reach up into a tree and pluck an apple compote, warm and ready to eat?

Beauty Tip

In the spirit of the Oscar Wilde quote above, take yourself out on a date to a cozy little café—and bring a book!

Lingering Question

Is there a friend from the past you need to reconnect with?

—

Dear Readers, I hope you enjoyed this one! Please leave a comment to let me know what you think, like this post if you enjoyed, and subscribe to Soul-Making for more!

Translated by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

This makes me want to run to the kettle! Thank you for sharing the interesting history of tea, from a fellow tea lover 💕

Thank you for sharing this. Wonderfully whimsical, yet educational and touching. I am glad the Spirit moved you to write this.